This is a rewrite of the zhihu article. Permission has been granted.

The original author of this article is finding a job, find him on GitHub.

What’s Type level programming, a.k.a type gymnastics?

TypeScript is a powerful and expressive language that allows you to write complex yet elegant code. Some TypeScript users love to explore the possibilities of the type system and love to encode logic at type level.

This practice, as we have a slang for it, is known as type gymnastics. Type gymnastics can help you to perform various tasks such as parsing, validating, transforming, or computing values based on types. Type gymnastics often requires the users mastering a wide range of advanced TypeScript features such as conditional types, recursive types, template literal types, mapped types and more. The community also helps users to learn type gymnastics by creating fun and challenges such as type challenges.

You can proudly call yourself a TypeScript magician if you can solve most of the type challenges!

The type-level programming community has been creating all kinds of amazing tricks ever since the introduction of template literal type in version 4.1. Some enthusiasts have pushed this hobby to the extreme, and even tried to reimplement TypeScript at compile-time using pure types!

However, there are still three major obstacles that prevent TypeScript becoming a true turing complete machine (#14833). They are:

- tail recursion count: the maximum number of recursive calls in a conditional type.

- type instantiation depth: the maximum depth when we instantiate a generic type alias.

- type instantiation count: the maximum number of type instantiations.

These limits are not arbitrary. The compiler has set a maximum limit for these three values and will throw an error TS2589 if we exceed them to prevent the compiler from hanging or crashing.

They are the walls that stop us from breaking through the limits of TypeScript compiler. But, there is actually a hidden layer behind the wall, if we explore the compiler source code carefully.

Doing type level programming is like casting magic, but breaking through the wall of type gymnastics is like finding the hidden chamber of secrets that contains the most powerful and dangerous type of all.

Some digression for background…

Back then three years ago, I wrote an article about how to implement a recursive descent parser. At that time, there was no template literal type, and a lot of type system limitations have been lifted since then. Crafting a code interpreter using recursive descent parsing would easily exceed the compiler’s limit.

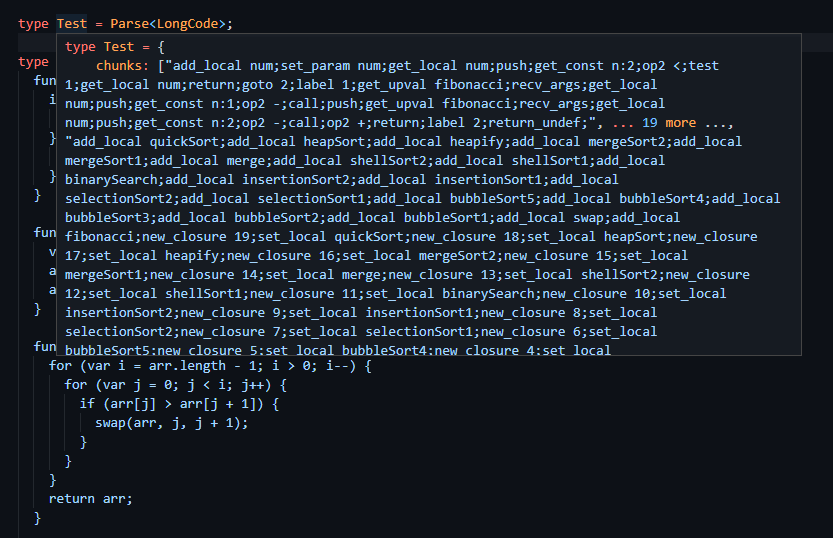

So I decided to switch to a bottom-up parsing method to more easily bypass the limit, with some tricks :). Later, as TypeScript gradually evolves, newly added features opened unprecedented possibilities of type gymnastics. This finally gave me a chance to implement a type gymnastics parser generator for LALR(1) grammar to generate a parser for a subset of JavaScript syntax.

I designed a special purpose “bytecode” for the ease of type level execution and directly compiled the input code into the bytecode during the parsing process(I still have some unfinished work left, procrastinating now…). My ultimate goal is to implement a type level scripting language that can execute sufficiently complex code.

To achieve this goal, I need to solve all the three limitations mentioned above to run lunatic code patterns, to some extent, at compile time!

Tail Recursion Count

Let’s look at the first limitation, the type tail recursion count (tailCount). Type level programming often uses recursive types. Before the previous versions supported recursive types, we usually implemented recursion by combining mapped types, recursive type definitions and index types. Ever since we had recursive types and tail recursion of type instantiation, this kind of type gymnastics became much more elegant, but at the same time we also got this tail recursion count limitation.

Searching for tailCount in the TypeScript source code, we can see that the implementation is related to computing conditional types. Let’s simplify the code a bit and take a look (sorry folks, I cannot get a link to GitHub source code due to checker.ts is too large):

1 | // transitively used in instantiateType |

We can see that as long as the branch of the conditional type that matches is another conditional type, and the new conditional type is neither a distributive conditional type nor a union type or never, then the new conditional type will be substituted into the next round of computation.

The only problem is that it will trigger an error TS2589 when the loop reaches 1000 times, TS Playground:

1 | type ZeroFill< |

To avoid reaching the 1000 times recursion limit, we can deliberately break the tail recursion after a certain number of recursions (using an extra parameter to count), as long as we return a type that does not satisfy the above conditions, and does not affect the result of the type we return, such as returning an intersection type (Playground Link):

1 | // Hard-code a number array, array index corresponds to value plus 1 |

Type Instantiation Depth

The type above has now exceeded the limit of 1000 recursions, but if you comment out Sized3K, you will see that Sized4K will trigger TS2589. This is related to the second limitation, which is the type instantiation depth (instantiationDepth). The reason why commenting out has an effect is because TypeScript will cache all instantiated types, which we will discuss later. Again, we can search for instantiationDepth in the TS source code. You can see that it is implemented with all types that have type mapping. There are several kinds of type mapping. For example, types that use generic parameters will have type mapping to map parameters to actual types. The relevant code is simplified as follows:

1 | function instantiateType(type?: Type, mapper?: TypeMapper): Type | undefined { |

We also see the instantiationCount mentioned at the beginning, but we will first focus on the instantiationDepth for now. We can see that before and after each type alias instantiation, the instantiation depth will increase and decrease, and any call to instantiateType in the middle process will indirectly call the above type, which will make the depth count continue to increase.

To avoid reaching the maximum depth, one is to use tail recursion as much as possible, and the other is to reduce the dependence on intermediate types in the recursive process if you use the technique of breaking tail recursion before.

Here is an example code (to reduce interference we simplify it to only have two generic parameters, only keep the recursive logic itself, and use intersection type to prevent tail recursion instantiation):

1 | // Simulate a type that keeps calculating values and sets the finish state based on the results |

In the example above, BadWay increases the depth by two levels more than GoodWay for each recursion, which will reach the recursion depth limit faster.

With the instantiation level limit, we should start recursion as early as possible, putting all kinds of intermediate type calculations into parameters. And let each iteration type complete instantiation as soon as possible, releasing the increased depth.

Another way to release the depth count in advance is to manually split the iteration process into multiple parts, storing intermediate result as a type alias.

Let’s take the first type as an example:

1 | type Sized3K = ZeroFill<[], 3000>; // Okay. |

One thing to keep in mind is that as the type becomes more complex, the tsc compiler may handle it fine, but the editor may not give any feedback due to the long response time. This is because they use different methods and caches for type checking. For example, in the code above, if we comment out Sized4K (which has a cache effect), and directly generate Sized5K from Sized3K, we will get a TS2589 error again. See the playground link.This is not caused by the two limitations we mentioned before, because this time we only have 2000 iterations, much less than Sized3K. The actual cause of this compilation error leads us to the third limitation: the type instantiation count (instantiationCount).

Type Instantiation Count

We have encountered the variable instantiationCount before in the function instantiateTypeWithAlias. It has a current limit of 5,000,000, which is incremented together with instantiationDepth every time a type is instantiated. Unlike instantiationDepth, it does not decrease when the instantiation is done because it represents the number of type instances that are created in one instantiation process. If we continue to search the source code, we can see that it is set to 0 when the compiler checks some types of syntax nodes:

1 | function checkSourceElement(node) { |

If we debug tsc and set a breakpoint after the condition instantiationCount >= 5000000, we will see in the call stack that the error is thrown when instantiating an object type with more than 3700 members. This object type is actually the array type that we generated. We will not analyze step by step why it produces so many (5 million) type instances here. We just need to know that this array is created by many generic parameters, which leads to a large number of type instances. Even if our type gymnastics did not generate such a large array, it would slow down the speed when producing so many type instances. So how can we avoid this situation?

The direct conclusion is to use other types to achieve the purpose according to the needs. For example, if you use an array type to simulate a stack structure, and only need to access the last one or a few elements, then you can define a List object type, which is concatenated, but the structure of the object is fixed:

1 | type List<T> = { data: T; prev: List<T> }; |

Alternatively we can encode the logic in string by constructing template string of a specific format.

1 | type Append<S extends string, T extends string> = `${T},${S}`; |

You can even use union types. However, you need to pay attention that when union types are used in distributive conditional types, they will generate the same number of type instances as the number of elements, but they are still a better choice in many cases.

Usual type level programming will not trigger this limitation, so we will not describe it too much. To optimize the number of instantiations, you inevitably need to read the compiler source code, or you can add the --diagnostics parameter when calling tsc, and observe the Instantiations in the output, which can show how many type instances are generated in total.

Conclusion

One caveat is that all tricks in the article are probably the byproduct of a specific compiler implementation and are not officially supported by the TypeScript team. And they may even be broken in the future!

Actually, most of these dark magics are manipulating type instantiation to make time-space trade-offs. We are nudging compiler to forget intermediate type caches (Obliviate!), prompting it to compute more types (Imperio!) and forcing it to work longer for a compilation (Incarcerous!). All the grueling rituals for the holy grail of turing completeness!

However, they are still very useful in some cases and help us break the limitations of TypeScript! The snake is in the chamber of secrets, so use these lost spells wisely, my great mage!

If you find this article useful, I would be more than happy if you can treat me some coffee.

Translation, rewrite and title image generation are all assisted by MicroSoft Bing Chat.