Benchmark TypeScript Parsers: Demystify Rust Tooling Performance

TL;DR: Native parsers used in JavaScript are not always faster due to extra work across languages. Avoiding these overhead and using multi-core are crucial for performance.

Rust is rapidly becoming a language of choice within the JavaScript ecosystem for its performance and safety features. However, integrating Rust into JavaScript tooling presents unique challenges, particularly when it comes to designing an efficient and portable plugin system.

“Rewriting JavaScript tooling in Rust is advantageous for speed-focused projects that do not require extensive external contributions.” - Nicholas C. Zakas, creator of ESLint

Learning Rust can be daunting due to its steep learning curve, and distributing compiled binaries across different platforms is not straightforward.

A Rust based plugins necessitates either static compilation of all plugins or a carefully designed application binary interface for dynamic loading.

These considerations, however, are beyond the scope of this article. Instead, we’ll concentrate on how to provide robust tooling for writing plugins in JavaScript.

A critical component of JavaScript tooling is the parsing of source code into an Abstract Syntax Tree (AST). Plugins commonly inspect and manipulate the AST to transform the source code. Therefore, it’s not sufficient to parse in Rust alone; we must also make the AST accessible to JavaScript.

This post will benchmark several popular TypeScript parsers implemented in JavaScript, Rust, and C.

Parser Choices

While there are numerous JavaScript parsers available, we focus on TypeScript parsers for this benchmark. Modern bundlers must support TypeScript out-of-the-box, and TypeScript is a superset of JavaScript. Benchmarking TypeScript is a sensible choice to emulate the real-world bundler workload.

The parsers we’re evaluating include:

- Babel: The Babel parser (previously Babylon) is a JavaScript parser used in Babel compiler.

- TypeScript: The official parser implementation from the TypeScript team.

- Tree-sitter: An incremental parsing library that can build and update concrete syntax trees for source files, aiming to parse any programming language quickly enough for text editor use.

- ast-grep: A CLI tool for code structural search, lint, and rewriting based on abstract syntax trees. We are using its napi binding here.

- swc: A super-fast TypeScript/JavaScript compiler written in Rust, with a focus on performance and being a library for both Rust and JavaScript users.

- oxc: The Oxidation Compiler is a suite of high-performance tools for JS/TS, claiming to have the fastest and most conformant parser written in Rust.

Native Addon Performance Characteristics

Before diving into the benchmarks, let’s first review the performance characteristics of Node-API based solutions.

Node-API Pros:

- Better Compiler Optimization: Code in native languages have compact data layouts, leading to fewer CPU instructions.

- No Garbage Collector Runtime Overhead: This allows for more predictable performance.

However, Node-API is not a silver bullet.

Node-API Cons:

- FFI Overhead: The cost of interfacing between different programming languages.

- Serde Overhead: Serialization and deserialization of Rust data structures can be costly.

- Encoding Overhead: Converting JS string in utf-16 to Rust’s utf-8 string can introduce significant delays.

We need to understand the pros and cons of using native node addons in order to design an insightful benchmark.

Benchmark Design

We consider two main factors:

File Size: Different file sizes reveal distinct performance characteristics. The parsing time of an N-API based parser consists of actual parsing and cross-language overhead. While parsing time is proportional to file size, the growth of cross-language overhead depends on the parser’s implementation.

Concurrency Level: Parallel parsing is not possible in JavaScript’s single main thread. However, N-API based parsers can run in separate threads, either using libuv’s thread pool or their own threading model. That said, thread spawning also incurs overhead.

We are not considering these factors in this post.

- Warmup and JIT: No significant difference observed between warmup and non-warmup runs.

- GC, Memory Usage: Not evaluated in this benchmark.

- Node.js CLI arguments: To make the benchmark representative, default Node.js arguments were used, although tuning could potentially improve performance.

Benchmark Setup

The benchmark code is hosted in ast-grep’s repo https://github.com/ast-grep/ast-grep/blob/main/benches/bench.ts.

Testing Environment

The benchmarks were executed on a system equipped with the following specifications:

- Operating System: macOS 12.6

- Processor: arm64 Apple M1

- Memory: 16.00 GB

- Benchmarking Tool: Benny

File Size Categories

To assess parser performance across a variety of codebases, we categorized file sizes as follows:

- Single Line: A minimal TypeScript snippet,

let a = 123;, to measure baseline overhead. - Small File: A concise 24-line TypeScript module, representing a common utility file.

- Medium File: A typical 400-line TypeScript file, reflecting average development workloads.

- Large File: The extensive 2.79MB

checker.tsfrom the TypeScript repository, challenging parsers with a complex and sizable codebase.

Concurrency Level

For this benchmark, we simulate a realistic workload by parsing five files concurrently. This number is an arbitrary but reasonable proxy to the actual JavaScript tooling.

It’s worth noting, to seasoned Node.js developers, that this setup may influence asynchronous parsing performance. However it does not disproportionately favor Rust-based parsers. The rationale behind this is left as an exercise for the reader. :)

This post aims to provide a general overview of the benchmarking for TypeScript parsers, focusing on the performance characteristics of N-API based solutions and the trade-offs involved. Feel free to adjust the benchmark setup to better fit your workload.

Now, let’s delve into the results of TypeScript parser benchmarking!

Results

Raw data can be found in this Google Sheet.

Synchronous Parsing

The performance of each parser is quantified in operations per second—a metric provided by the Benny benchmarking framework. For ease of comparison, we’ve normalized the results:

- The fastest parser is designated as the benchmark, set at 100% efficiency.

- Other parsers are evaluated relative to this benchmark, with their performance expressed as a percentage of the benchmark’s speed.

TypeScript consistently outperforms the competition across all file sizes, being twice as fast as Babel.

Native language parsers show improved performance for larger files due to the reduced relative impact of FFI overhead.

Nevertheless, the performance gains are not as pronounced due to serialization and deserialization (serde) overhead, which is proportional to the input file size.

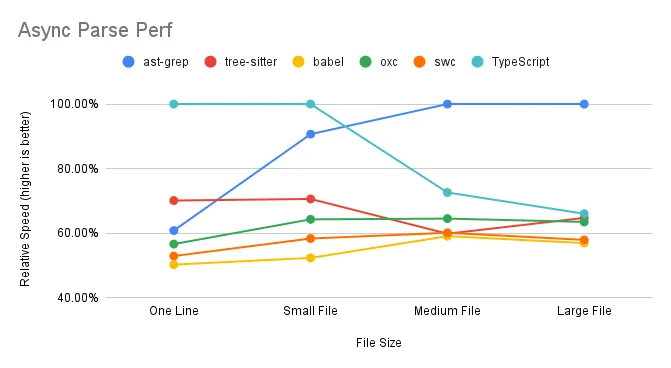

Asynchronous Parsing

In the asynchronous parsing scenario, we observe the following:

ast-grep excels when handling multiple medium to large files simultaneously, effectively utilizing multi-core capabilities. TypeScript and Tree-sitter, however, experience a decline in performance with larger files. SWC and Oxc maintain consistent performance, indicating efficient use of multi-core processing.

Parse Time Breakdown

When benchmarking a Node-API based program, it’s crucial to understand the time spent not only executing Rust code but also the Node.js glue code that binds everything together. The parsing time can be dissected into three main components:

1 | time = ffi_time + parse_time + serde_time |

Here’s a closer look at each term:

ffi_time(Foreign Function Interface Time): This represents the overhead associated with invoking functions across different programming languages. Typically,ffi_timeis a fixed cost and remains constant regardless of the input file size.parse_time(Parse Time): The core duration required for the parser to analyze the source code and generate an Abstract Syntax Tree (AST).parse_timescales with the size of the input, making it a variable cost in the parsing process.serde_time(Serialization/Deserialization Time): The time needed to serialize Rust data structures into a format compatible with JavaScript, and vice versa. As withparse_time,serde_timeincreases as the input file size grows.

In essence, benchmarking a parser involves measuring the time for the actual parsing (parse_time) and accounting for the extra overhead from cross-language function calls (ffi_time) and data format conversion (serde_time). Understanding these elements helps us evaluate the efficiency and scalability of the parser in question.

Result Interpretation

This section offers a detailed and technical analysis of the benchmark results based on the parse time framework above. Readers seeking a high-level overview may prefer to skip ahead to the summary.

FFI Overhead

In both sync parsing and async parsing scenario, the “one line” test case, which is predominant FFI overhead with minimal parsing or serialization, shows TypeScript’s superior performance. Surprisingly, Babel, expected to excel in this one-line scenario, demonstrates its own peculiar overhead.

As file size increases, FFI overhead becomes less significant, as it’s largely size-independent. For instance, ast-grep’s relative speed is 78% for a large file compared to 72% for a single line, suggesting an approximate 6% FFI overhead in synchronous parsing.

FFI overhead is more pronounced in asynchronous parsing. ast-grep’s performance drops from 72% to 60% when comparing synchronous to asynchronous parsing of a single line. The absence of a notable difference in performance for swc/oxc may be due to their unique implementation details.

Serde Overhead

Unfortunately, we failed to replicate swc/oxc’s blazing performance we witnessed in other applications.

Despite minimal FFI impact in “Large file” test cases, swc and oxc underperform compared to the TypeScript compiler. This can be attributed to their reliance on calling JSON.parse on strings returned from Rust, which is, to our disappointment, still more efficient than direct data structure returns.

Tree-sitter and ast-grep avoid serde overhead by returning a tree object rather than a full AST structure. Accessing tree nodes requires invoking Rust methods from JavaScript, which distributes the cost over the reading process.

Parallel

Except tree-sitter, all native TS parsers have parallel support. Contrary to JS parsers, native parsers performance will not degrade when concurrently parsing larger files. This is thanks to the power of multiple cores. JS parsers suffer from CPU bound because they have to parse file one by one.

Perf summary for parsers

The performance of each parser is summarized in the table below, which outlines the time complexity for different operations.

In the table, constant denotes a constant time cost that does not change with input size, while proportional indicates a variable cost that grows proportionally with the input size. An N/A signifies that the cost is not applicable.

JS-based parsers operate entirely within the JavaScript environment, thus avoiding any FFI or serde overhead. Their performance is solely dependent on the parsing time, which scales with the size of the input file.

The performance of Rust-based parsers is influenced by a fixed FFI overhead and a parsing time that grows with input size. However, their serde overhead varies depending on the implementation:

For ast-grep and tree-sitter, they have a fixed serialization cost of one tree object, regardless of the input size.

For swc and oxc, the serialization and deserialization costs increase linearly with the input size, impacting overall performance.

Discussion

Transform vs. Parse

While Rust-based tools are renowned for their speed in transpiling code, our benchmarks reveal a different narrative when it comes to converting code into an AST that’s usable in JavaScript.

This discrepancy highlights a critical consideration for Rust tooling authors: the process of passing Rust data structures to JavaScript is a complex task that can significantly affect performance.

It’s essential to optimize this data exchange to maintain the high efficiency expected from Rust tooling.

Criteria for Parser Inclusion

In our benchmark, we focused on parsers that offer a JavaScript API, which influenced our selection:

- Sucrase: Excluded due to its lack of a parsing API and inability to produce a complete AST, which are crucial for our evaluation criteria.

- Esbuild/Biome: Not included because esbuild functions primarily as a bundler, not a standalone parser. It offers transformation and build capabilities but does not expose an AST to JavaScript. Similarly, biome is a CLI application without a JavaScript API.

- Esprima: Not considered for this benchmark as it lacks TypeScript support, which is a key requirement for the modern JavaScript development ecosystem.

JS Parser Review

Babel:

Babel is divided into two main packages: @babel/core and @babel/parser. It’s noteworthy that @babel/core exhibits lower performance compared to @babel/parser. This is because the additional entry and hook code that surrounds the parser in the core package. Furthermore, the parseAsync function in Babel core is not genuinely asynchronous; it’s essentially a synchronous parser method wrapped in an asynchronous function. This wrapper provides extra hooks but does not enhance performance for CPU-intensive tasks due to JavaScript’s single-threaded nature. In fact, the overhead of managing asynchronous tasks can further burden the performance of @babel/core.

TypeScript:

The parsing capabilities of TypeScript defy the common perception of the TypeScript compiler (TSC) being slow. The benchmark results suggest that the primary bottleneck for TSC is not in parsing but in the subsequent type checking phase.

Native Parser Review

SWC:

As the first Rust parser to make its mark, SWC adopts a direct approach by serializing the entire AST for use in JavaScript. It stands out for offering a broad range of APIs, making it a top choice for those seeking Rust-based tooling solutions. Despite some inherent overhead, SWC’s robustness and pioneering status continue to make it a preferred option.

Oxc::

Oxc is a contender for the title of the fastest parser available, but its performance is tempered by serialization and deserialization (serde) overhead. The inclusion of JSON parsing in our benchmarks reflects real-world usage, although omitting this step could significantly boost Oxc’s speed.

Tree-sitter

Tree-sitter serves as a versatile parser suitable for a variety of languages, not specifically optimized for TypeScript. Consequently, its performance aligns closely with that of Babel, a JavaScript-focused parser implemented in JavaScript. Alas, a Rust parser is not inherently faster by default, even without any N-API overhead.

A general purpose parser in Rust may not beat a carefully hand-crafted parser in JavaScript.

ast-grep

ast-grep is powered by tree-sitter. Its performance is marginally faster than tree-sitter, indicating napi.rs is a faster binding than manual using C++ nan.h.

I cannot tell whether the performance gain is from napi or napi.rs but

Leveraging the capabilities of tree-sitter, ast-grep achieves slightly better performance, suggesting that napi.rs offers a more efficient binding than traditional C++ nan.h methods. While the exact source of this performance gain—whether from napi or napi.rs—is unclear, the results speak to the effectiveness of the implementation. Or put it in another way, Broooooklyn is 🐐.

Native Parser Performance Tricks

tree-sitter & ast-grep’ Edge

These parsers manage to bypass serde costs post-parsing by returning a Rust object wrapper to Node.js. This strategy, while efficient, can lead to slower AST access in JavaScript as the cost is amortized over the reading phase.

ast-grep’s async advantage:

ast-grep’s performance in concurrent parsing scenarios is largely due to its utilization of multiple libuv threads. By default, the libuv thread pool size is set to four, but there’s potential to enhance performance further by expanding the thread pool size, thus fully leveraging the available CPU cores.

Future Outlook

As we look to the future, several promising avenues could further refine TypeScript parser performance:

Minimizing Serde Overhead: By optimizing serialization and deserialization processes, such as employing Rust object wrappers, we can reduce the performance toll these operations take.

Harnessing Multi-core Capabilities: Effective utilization of multi-core architectures can lead to substantial gains in parsing speeds, transforming the efficiency of our tooling.

Promoting AST Reusability: Facilitating the reuse of Abstract Syntax Trees within JavaScript can diminish the frequency of costly parsing operations.

Shifting Workloads to Rust: The creation of a domain-specific language (DSL) tailored for AST node querying could shift a greater portion of computational work to the Rust side, enhancing overall efficiency.

These potential improvements represent exciting opportunities to push the boundaries of Rust tooling in parsing performance.

Hope this article helps you! We can continue to innovate and deliver even more powerful tools to the developer community!